- Home

- Laurence Myers

Hunky Dory (Who Knew) Page 2

Hunky Dory (Who Knew) Read online

Page 2

The site of the Finsbury Park Empire is now a mosque where Abu Hamza, the infamous cleric with the hook for a hand, once preached his particular brand of brotherly love. On the spot where the cleric more recently spewed venom, Arthur Askey, Jimmy James, Jimmy Wheeler, Max Wall and a host of other legendary comedians spewed jokes. These artistes toured the UK and usually played any particular theatre once a year so never had to change their act, and we would have hated it if they did. The comedians’ routines, polished and refined by years of practice, were eagerly anticipated and if one was missed we fretted. Their acts were so good that over sixty years later I can still recite chunks out of most of them, and to my wife’s dismay I frequently do. Their example taught me to insist that the acts that I managed always featured their hits in live performance, no matter how bored they were with performing them. ‘Give your audience what they want.’

My favourite singer was Josef Locke: a large, usually drunk, Irish tenor with the voice of an angel. His big song was ‘The Soldier’s Dream’. There was a line in the song where he put his hand to his ear and shouted: ‘Hear the guns’ and we, the cognoscenti in the audience, shouted it out with him. I have tortured my children and, indeed, selected friends to this day by insisting on playing the song from my iTunes collection and expecting them to holler ‘Hear the guns’ at the appropriate moment.

Josef Locke did not believe in paying tax. In order to keep ahead of the Inland Revenue he would perform his sell-out concerts billed as Mr X. In 1991, Ned Beatty played him in a film called Hear My Song. Any of my kids who didn’t go to see that film would have been cut out of my will. If you don’t buy the DVD, you’ll be cut out as well.

Comedian Max Wall was a particular favourite. He announced himself with: ‘The name’s Wall, Max Wall, my uncle was the Great Wall of China.’ He used to come on stage clown-like as Professor Wallofski, sporting a long and wild wig, wearing black tights and slap shoes. His absolute showstopper was the Max Wall walk. It is impossible to describe his act and I urge you to look him up on YouTube. His career was ruined in 1955 when, as a married man, he was caught in bed with Miss Great Britain, twenty-six years his junior – something that today would guarantee him a book deal, a spread in Hello! and a spot in Celebrity Something-or-Other.

In 1974 when he was quite old, I filmed his classic Professor Wallofski act at the Richmond Theatre before an invited audience, which included Richard Attenborough and many other celebrities, all devoted fans of Max. Max was a bankrupt and I paid him in cash, which he said ‘saved his life’. He was also working by that time as a serious actor. I went to see him in John Osborne’s The Entertainer. He was magnificent and a reviewer said, ‘Max Wall makes Olivier look like an amateur.’ Max died in 1990, but there is still a Max Wall Society and I have given them permission to distribute Max Wall Funny Man, the film I lovingly made, to its members.

From the age of eleven I received a steady education at Holloway grammar school, a ten-minute bus ride from home. My popularity there, I’m sure, had little to do with my parents owning a sweet shop and sweets being rationed until 1953!

After an undistinguished school career, I left at sixteen with a modest six O-levels. I had no idea what I wanted to do, other than becoming a Latin American percussionist. My preferred dream would have been to be a drummer but I could only afford to buy a set of bongos, hence the Latin American bias. Telling my mother that I wanted to be a drummer of any sort would have been an intriguing way to commit suicide, so I did not even suggest it. I had to choose from the post-war Jewish Mother’s List: doctor, lawyer, architect, dentist, accountant. This was very brave on my parents’ part as none of these professions provided a living prior to qualification and it was going to be a struggle for them to support me. I went down the list, rejecting the suggested professions for no sensible reasons. My mother threatened me with a career in hairdressing if I did not say yes to something, so I agreed to accountancy.

I became an articled clerk to a small firm of chartered accountants in Holborn. The firm consisted of two brothers, and I was their first and only employee. They did not even have a secretary and did all of their own typing. They were very nice men, but the practice was tiny and I received no real training. At a time when a sixteen-year-old school leaver was earning about five pounds a week, my pay was a Dickensian fifteen shillings, seventy-five pence in today’s currency. Hard to believe now, this covered my daily fares of one shilling (five pence), and lunch money of two shillings (ten pence). It was a long time ago.

I earned the occasional few shillings as a newspaper reporter. Well, more of a tiny cub reporter. The Daily Express used to pay for contributions and if I saw a road accident I would call them from the nearest phone box, exaggerate the severity of the incident and get sent a five-shilling postal order. I used to walk about hoping to see a car crash, preferably fatal. Well, I was young and very broke.

As my parents could not afford to subsidise me, I earned my spending money working on Sundays in the street market on Club Row Waste, an extension of the famous Petticoat Lane market in London’s East End. Sunday was a big, busy day in the Astoria Candy Stores so after the market I helped out in the shop. I was no martyr, my parents worked hard and so did I. In the market I rented a stall from which I sold mainly old confectionery provided by my father’s connections. This was before the concept of sell-by dates, which is just as well, because most of my stock would have had Roman numerals. True to the Finsbury Park ethos of dealing in hooky gear, a man only known to me as Cecil delivered my more current stock to our shop in the middle of the night. I never questioned the source of the remarkably cheap and invoice-free goods.

In the summer I sold cold drinks from a large, galvanised tin bath on which I balanced a huge block of ice. The ice, which was extremely heavy, was schlepped by my only employee, Reg, aka Chicken. It was a ten-minute walk with the ice water melting on his back, from an ice factory in not so nearby Wentworth Street. Chicken was an illiterate meat-market porter, who could be the subject of his own book as well as many a police charge sheet. I went to his wedding to a hooker who was pregnant with twins. Chicken proudly claimed that ‘one’s mine an’ one’s me mate’s.’

Market grafting is only romantic to those who have never done it out of necessity. For me it involved borrowing a vehicle that may or may not start; loading up at six o’clock on Sunday morning come rain, shine or flu; and struggling to make about five pounds, and there’s not much romance in that. It was, however, a most valuable part of my education, and the fiver a week that I earned kept me in spending money. I could also afford my first set of wheels, but only two of them, on a Lambretta motor scooter. It cost about eighty pounds; more money than I had ever possessed, so I bought it on hire purchase.

After a couple of years I became a multiple retailer, having rented a second stall on Club Row, an adjacent market, the stall manned for me by my pal Colin Levine. The doubling of my business outlet enabled me to double my wheels from two to four and I bought an Italian-made Isetta bubble car. Messerschmitt also made a bubble car but in those days Jewish people did not buy German cars or any cars that were green. The German antipathy was because of the recent war and green was considered to be unlucky.

Market grafters are a fascinating bunch of characters. Some, anecdotally, did so well that when they drove home to their mansions in the country, they swapped their beat-up old vans for their Rolls-Royces. On one occasion, the rarely seen but legendary Red-Faced Sam came to the market to work the ‘run-out’, a fraudulent auction resulting in some poor punter going home with a box full of swag (worthless junk) for which they had handed over their Christmas Club savings. I saw him avoid repaying a very large and very angry husband of a woman he had conned, who caught him as he was packing up. Sam explained, as well as he could with a docker’s hand around his windpipe, that he would love to give a refund but he had ‘closed the books for the purchase tax’ and would get into trouble with the authorities if he gave the money back today. The docker,

suckered by Sam’s patter, and clearly ready to join up against the authorities, apologised profusely and agreed to return next week for the promised ‘no-questions-asked full refund’. Needless to say, Sam had no plan to return to the market for some years.

Most market grafters had a philosophy that was ‘As long as they don’t cut my tongue out, I’ll earn a living selling something.’ I had a huge, warm duffel coat, which I wore for the cold winter mornings. It was really scruffy but even after I was married I kept it in my cupboard for some years until I felt confident that I could earn a living as an accountant. Some market grafters went to jail, some prospered, and one became Alan Sugar.

In 1948, when I was twelve, my brother Roger was born. At that time it was not unusual to have a large gap between children. The threat of war delayed families having children, and they were inclined to wait a few years after the war before starting again. Roger was a gorgeous baby and I loved him to bits. I still do. We were obliged to share a bedroom until I was about eighteen, but I never for one moment resented him. When I was sixteen I ventured up west to the Queensway ice skating rink, sometimes taking the cute four-year-old Roger with me as a pulling prop. It worked, and there I met fourteen-year-old Marsha Bloom, who would be my intermittent girlfriend for some ten years and, ultimately, my wife.

Marsha lived just off the Edgware Road. I called it Paddington but she called it Marylebone. The argument persists to this day but it was undeniably classier than Finsbury Park, and her family was so posh they had fruit on the table when nobody was ill. We were married in 1962 and – more than half a century later – she is still the love of my life.

My father’s shop did well with the sweets and cigarettes because of the queue that formed outside of the cinema opposite. In the fifties there was no competition from television and everybody went to the cinema at least once a week. The Astoria was full every evening no matter what was showing, and the lines would form early. Sweets were on ration and had to be weighed up for sale out of seven-pound jars. Rationing required cutting out coupons for each sale, and from the age of eleven I had to work in the shop every evening to deal with the cinema pre-opening rush. I’m sure that I can still pick out a handful of sweets to weigh a quarter of a pound with great accuracy.

On the actual day that sweet rationing ended in 1953, we sold every single sweet in the shop. The shelves were absolutely bare and for some weeks to follow we opened for just an hour a day to sell the little stock my father had managed to find. Unlike now, where concessions are the major money-earner for cinemas, the venue itself did not need the revenue from selling any drinks or snacks. With rationing ended and TV inexorably taking cinema audiences, so the owners looking for more income introduced kiosks selling packaged sweets.

The disappearance of the cinema audience market caused the inevitable demise of the Astoria Candy Stores and in 1954 my father was about to go broke. It was not only our business that was threatened; it was also our home as we lived above the shop. My father was incapable of dealing with this, so aged eighteen, I had to. I went to Uncle Len, my father’s brother-in-law, and begged him to help out financially, which he generously did. I went to see the bank manager and persuaded him not to foreclose. This episode took away what little confidence my father had and, at eighteen, I effectively became head of the family. We put a little hairdressing salon on the ground floor behind the shop and, enduring the physical pain from her bad leg, my mother went back to work as a hairdresser. For a while, my father still ran the sweet shop at the front. To accommodate the salon, we lost our bathroom and our only bath was moved to the middle of the kitchen. They say that you should never be ashamed of your own home, but I was acutely embarrassed at the thought of my friends seeing this.

After a couple of years we sold the shop, and my parents opened a proper salon in a parade of shops in nearby Manor House, where we rented a flat in the block above. Still living above the shop, but least I now had my own bedroom, and the bath was in the bathroom. My father – who had been such a lousy hairdresser before the war – now worked alongside my mother and eventually got back a little of his confidence and self-respect.

3. MANNERS MAKETH A MAN BUT A DARK SUIT DOES NOT MAKETH AN ACCOUNTANT

I am still entitled to use the initials FCA – Fellow of the Institute of Chartered Accountants – after my name, although I cannot remember the last time I did so. Each year when it is time to pay the annual subscription, I wonder why I am spending the few hundred pounds that it costs to continue membership. Then I think about how hard it was for me to get the qualification, and pay up.

I found studying for my exams really hard. We were prepared for exams by correspondence courses, which required great self-discipline, which I had heard about but did not have. I was supposed to study for an average of three hours an evening. I would tell my parents that I was going to the public library to study but then spend the time at friends’ houses, listening to music or going to a film. At weekends, when not helping in the shop, I spent my evenings at clubs like The Poubelle, Cy Laurie’s, the El Toro, the Whisky A Go-Go and the Cage D’or, perfecting my jive and bongo playing. Few of these clubs had licences to sell alcohol, it cost little to get in, and they were mostly rather grotty but I went to them because I loved to dance.

There is an unfair generalisation that accountants are boring. People can be boring no matter what their job is. I have known some famous actors who are really boring off-stage. However, I found that there was no quicker way of stopping the irritatingly chatty person sitting next to me on a plane than answering the inevitable ‘and what is it that you do?’ with: ‘I’m an accountant.’ If this did not work, I used to add, ‘with the Inland Revenue’ … at which point they would move seats.

My lack of fascination with the structure of consolidated balance sheets meant that I struggled with my accountancy exams. There were intermediate and final exams that had to be passed, with six papers in each of the different subjects. If you failed in one, you had to take all six again. I twice failed one paper in each of the exams, resulting in my taking two years longer than necessary to qualify. For me, the problem of those years was that my life was on hold until I qualified, and there was no certainty that I would do so. I eventually earned my qualification at the end of 1960, and the day that my results came through was the most emotional day of my life. I started my proper grown-up life by becoming engaged to Marsha Bloom, the gorgeous girl that I had first met at the ice rink some ten years before.

4. THE EARLY SIXTIES – QUALIFIED, BUT FOR WHAT?

Whilst I was engaged to Marsha, Cyril Myers, a distant cousin, approached me with an opportunity to operate bingo one evening a week at the Rio cinema on Canvey Island. Showbiz called!

Cyril was an extremely nice guy about the same age as me. With a loan of four hundred pounds from Marsha’s stepfather, the lovely Billy Levene, we ventured east to Canvey Island. It’s a small mass in the Thames Estuary joined, I do not recall how, to the mainland. Canvey Island in the winter was decidedly lacking in sun-seekers and indeed sun. In the sixties, it was a drab wilderness of caravan parks and miserable stony beaches. The Rio cinema, a local fleapit, was generally patronised by holidaymakers and did not operate in the winter. Bingo was just becoming a big business, so where could we go wrong? Read on and find out.

We had an ambitious marketing campaign consisting of a couple of tiny ads in the local paper and a hand-made sign outside of the cinema. On our first night Cyril and I waited for the rush. Twenty-seven people – mostly Essex ladies with a definite resemblance to Les Dawson in drag – rushed to join the club and we were in business … sort of. I was the bingo caller, an experience which soon eradicated the tiny voice inside me that thought I could entertain in public. I had learned the bingo lingo: ‘two fat ladies, eighty-eight’, etc, and also decided that the way to build the audience was to tell a few jokes. I can tell you now that Jewish humour does not travel to Canvey Island. Our highest crowd was about sixty and we never made enough to pa

y the rent.

The law at the time was that you had to be a member of a club for twenty-four hours before you could actually play. This was to avoid the ladies going wild and squandering their sixpences without time to reflect on their folly. We were so short on punters that I let a middle-aged lady in without her having waited the statutory twenty-four hours. She was strangely pedantic. ‘So, you are letting me in without my having to wait for the statutory twenty-four hours?’ This should have rung a warning bell, but we were so short of members, I just patted her bum in a ‘cheekychappy’ way and waved her through.

The Essex constabulary force had a female sergeant of middleage who looks like Dot from EastEnders. I was charged with offences against the Gaming Act and I had visions of headlines in the popular press along the lines of ‘Chartered accountant in bingo scandal’ ruining my future chances of a knighthood. In the event, my cousin Cyril, being a gentleman, took the main rap and I was fined five pounds for contravening the Gaming Act. Cyril was fined fifty pounds and that was the end of our bingo empire. Had I not been busted, I am convinced that we could have doubled our miserable attendance to about a miserable hundred and I could today still be calling, ‘Number one, Kelly’s eye,’ to an adoring crowd of elderly ladies in Canvey.

5. HOW GOODMAN MET MYERS AND GOODMAN MYERS & CO., CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS, WAS BORN

Having had a very poor training at the firm to which I was articled, coupled with my great disinterest in accountancy, I was untrained and fearful of holding down a job. I decided that the best option was to be my own boss so that only me could fire me.

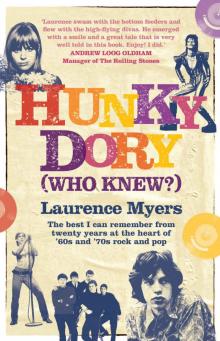

Hunky Dory (Who Knew)

Hunky Dory (Who Knew)