- Home

- Laurence Myers

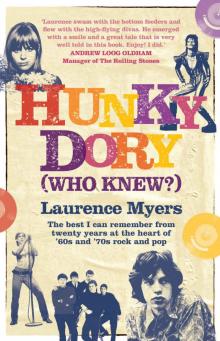

Hunky Dory (Who Knew)

Hunky Dory (Who Knew) Read online

First published in 2019 by B&B Books

Copyright © Laurence Myers 2019

The moral right of Laurence Myers to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. However, the publisher will be glad to rectify in future editions any inadvertent omissions brought to their attention.

ISBN 978-1-912892-29-7

Also available as an ebook

ISBN 978-1-912892-28-0

Jacket photography: Getty Images

Front cover images of Mick Jagger and Marianne Faithfull

copyright Gered Mankowitz

Typeset by Tom Cabot/ketchup

Cover design by Simon Levy

Project management by whitefox

Printed and bound by Clays

Hunky-dory

[Huhng-kee-daw-ree]

adj. informal

Fine: going well

Oxford English Dictionary

For

(in order of appearance)

Marsha,

James, Peter, Beth

CONTENTS

Introduction

1. The Forties – The War Years

2. The Fifties – The Finsbury Park Years

3. Manners Maketh a Man But a Dark Suit Does Not Maketh an Accountant

4. The Early Sixties – Qualified, But for What?

5. How Goodman Met Myers and Goodman Myers & Co., Chartered Accountants, Was Born

6. Mickie Most – My Parachute into the Heart of the London Music Scene

7. Don Arden

8. Midem – The Music Industry Annual Get-Together

9. Allen Klein – The Man Who Changed the Business of the Business

10. The Greek Tycoon

11. Pirate Radio and The Star-Club

12. Tetragrammaton Records and Tiny Tim

13. The Later Sixties – Showbiz, Here I Am!

14. The Society of Distinguished Songwriters – The SODS

15. Tony Macaulay

16. Music Publishers, Freddy Bienstock and Elvis

17. The Rolling Stones

18. Rupert Loewenstein Comes on the Scene and The Stones Break with Klein

19. The Jeff Beck Band and Rod Stewart

20. The Beatles and Apple Corp

21. Mike Leander – the Man Who Encouraged Me to Change my Business Life

22. Gem Productions – Mike Leander, Tony Macaulay

23. David Bowie

24. The Plan to Launch Bowie

25. Stevie Wonder – An Interlude in the Bowie Story

26. Postscript on David Bowie and Tony Defries

27. GTO including David Joseph and The New Seekers

28. Arcade Records

29. Mike Leander – Rock and Roll Pt. 2

30. GTO Records – Dick Leahy, Donna Summer, Billy Ocean, Heatwave

31. Gem Records – My Swan Song in the Record Business

Acknowledgements

Illustrations

Index

INTRODUCTION

Once upon a time, a long time ago, a young ex-student of the London School of Economics sat at my desk in my Regent Street office. He was a nice young man, skinny with long hair and a distinctively large mouth. He was a singer with a band; I was his accountant and he was interested in pensions.

‘After all, Laurence, I’m not going to be singing rock’n’roll when I’m sixty,’ he said in his south London accent.

‘No, you’re not,’ I agreed. How we laughed at the thought … Nearly sixty years on, my client – Mr Jagger – is not only still singing rock’n’roll, he is still fronting the greatest rock’n’roll band in the world – and he certainly does not live off a pension.

Six years after that meeting, another skinny young man with long hair, also a singer, sat opposite me at a different desk. I was no longer an accountant. I was managing artists. I thought that he was extremely talented but one thing slightly troubled me. Although his wife was by his side, he was clearly flirting with androgyny. It was the received wisdom of the times that it was mostly teenage girls who bought records, so their pin-ups should be handsome in an alpha-male way. After I agreed to take him on, I asked the young David Bowie his views on this.

‘Don’t you worry about that, Laurence,’ he said, ‘I know what I’m doing.’ And he did …

A music-business journalist once asked me: ‘What was it like to be at the heart of the British music industry in the fantastic sixties and seventies?’ I truthfully answered, ‘Who knew?’ At the time, although the people I was dealing with on a day-to-day basis were exciting and interesting, I had no idea that – years later – many of them would be of historic interest and that much of the music I was then involved with would still be relevant more than fifty years later.

They say that, in life, timing is everything and 1964 was the perfect time for me to get involved with the music business. The rock/pop business had burst into the public psyche with a four-to-the-floor drumbeat thumping out the rhythm of a youth revolution. In America young men were burning their draft cards as a protest against the ongoing war in Vietnam. Youth in the UK were rebelling against the general mess that they were going to inherit from the post-war generation – the established class system that pigeon-holed the populace according to their accents and anything else that would upset their parents – especially their taste in music.

Unlike today, when a kid can make a record in his bedroom, records had to be made in expensive recording studios. Record sales, along with the rest of the economy, were booming. The major record companies had a total lock on the recording industry and took advantage of the artists who were providing the music that reflected the desires of the youth of the day – which were, largely, sex and dancing. The contraceptive pill had been introduced in 1961, encouraging the sixties to swing. ‘Let’s spend the night together,’ suggested the Rolling Stones, and many did.

There was a real need for young business brains that would protect the artist against the rapacious practices of the record companies. Whom, you may ask, was amongst the first to fill this need? Twenty-eight-year-old me! How, you may ask, did I begin? Well, here’s how – although if, like me, you sometimes skip the early years chapters in biographies, go straight to chapter six. I won’t be offended.

1. THE FORTIES – THE WAR YEARS

I was born in London in 1936 within the sound of the Bow bells. This means that technically I am a cockney, but I spurned my birthright as soon as I could toddle, already hating the idea of having to learn to walk with shoulders rolling, thumbs in my braces, doing ‘The Lambeth Walk’ and shouting ‘Oi!’ Besides, I didn’t think that when I grew up I’d want to wear suits that were covered in pearl buttons. Little did I know that through the eras of teddy boys, flower power, glam rock, new romantic and punk, I’d flirt with far worse.

I was three years old when what my generation call ‘The War’ broke out. It was The War because, like the misnamed ‘The War to End All Wars’ twenty-odd years before it, there was only one war that made the papers. I recently read that currently there are people trying to kill each other in something like three hundred ‘conflicts’ – as little wars are called – around the world. There is also, of course, the global war against terrorism. Will we ever learn? It seems, sadly, not.

War can be fun … if you are a child and protected from its true tragedy by your parents. For my contemporaries an

d me it was an ever-changing adventure. Too many changes of schools to take education seriously, and no expectancy to do well. Lots of disruptions from air-raid warnings, fire drills, gas mask practice and, of course, many bomb sites to play on. All wonderful stuff but, to this day, if I ever hear a siren that has been programmed to sound like a wartime air-raid warning, my stomach turns.

Like most kids during the war years, I went to a variety of schools. Between 1940 and 1945 I attended a convent in Hitchin, Hertfordshire, a boarding school in High Wycombe, a school in Soho for refugee kids from Malta and a school for future gangsters in East Ham. There were other schools that I was sent to for just a few days, as I was shunted around the country so that Hitler could not find out where I was.

My father’s parents came from Russia and my mother’s parents came from Poland and they were both very influenced by the Fiddler On The Roof experiences of their recent heritage, when Jews were thrown out of countries just for being Jews. This was a generation that generally instilled in their children a need to have their own businesses because:

A) You could not get rich working for someone else. Being rich was perceived as the best insulation from anti-Semitism.

B) It was feared that anti-Semitism would inhibit the advancement of Jews working in the general marketplace.

This was not as paranoid as you might think. In the 1930s, National Socialism was politically and physically active against the Jews in Germany, and Mosley’s fascists were gaining traction in the UK. The ‘ruling classes’ may not have been overtly anti-Semitic, but the cooks in the stately homes of England had no need to learn how to make chicken soup or kosher salt beef for expected Jewish guests, unless the guest was a Rothschild, which supports A) above.

In 1939 when the war started, my parents were operating a small hairdressing salon on the Barking Road, East Ham. During the war my mother Alice, a wonderful woman whom I adored and respected, battled on to operate the salon during my father Gerry’s absence in the army. Our home was above the shop – a proud Jewish tradition that meant she could work all hours to make ends meet: an even prouder Jewish tradition.

I loved my father but found it hard to respect him. He was something of a Willy Loman figure, the titular character of Miller’s Death of a Salesman, who relied on being liked to get him through life, happily allowing my mother to be the strength of the family. He was adorable and one of the funniest men I have ever known. He used to send me letters from ‘your Daddy at the Front’. The ‘Front’ being the beach-front, Cleethorpes, the seaside town where he was safely stationed away from the London Blitz being endured by his wife and child.

According to my father, on one occasion when his platoon was strung out along the coastal terrain during one of the many invasion scares, he dropped his rifle, which fired a round. Anxious not to frighten his fellow soldiers, he shouted out: ‘Don’t worry, it’s me, Gerry!’ By the time the message was passed along to the ninth lookout, it had Chinese-whispered into a panicky: ‘It’s Gerry,’ which was of course one of the slangy names for Germans. The alarm was raised, barracks were mobilised, Winston Churchill probably scrambled into his siren suit, and my father was lucky to only be punished with guard duty for a month.

Towards the end of the war, having feigned madness to avoid being posted abroad to Singapore where bullets were being exchanged in anger, he was committed to an army mental hospital in Bristol. Here there were three categories of inmates: the poor unfortunate, genuinely ill; the malingerers like Dad trying to get out of the army; and the army spies planted to try to distinguish one from the other.

Family legend has it that he conducted an orchestra that had no instruments and that he fired the second violin for playing the wrong note. There’s a bad-taste sitcom in that story somewhere. In later years I asked my father how he, as a Jew, could not possibly wish to fight fascism, something that I was secretly ashamed of. He told me that the anti-Semitism in the British army was so strong that, in action, more Jews were shot in the back than the front. I am sure that this was not true, but I am equally sure that many Jews got a hard time from some other servicemen.

Whilst my father was fighting for democracy in the Palais de Dance in Cleethorpes, back in war-torn, dangerous London my mother and I lived between the shop in East Ham and the central London home of my maternal grandparents Peter and Annie Levenberg. My grandparents lived in a large flat in Bedford Square in the now trendy area of Bloomsbury. One of my earliest memories is clinging to my mother in a taxi as we drove there from East Ham through the blazing London docks during the Blitz. Grandpa Peter was a master tailor in the Mile End Road. I used to love going to his workshop where he and my uncle David would sit cross-legged on a counter, making bespoke suits built to outlast the Taj Mahal. There were huge heated pressing irons hissing on a gas range, the workshop smelled of tailor’s soap, and I was allowed to sit cross-legged with my grandpa, pulling out basting stitches with an ivory pick.

When I was aged six or seven, my mother would often put me alone on the 106 bus at East Ham for my grandmother to meet me an hour later at the Tottenham Court Road stop, where the conductor to whom I had been entrusted would help me off. No thought of danger from strangers … different days.

Tottenham Court Road tube station was the nearest designated bomb shelter to Bedford Square. The trains stopped running, the electric rails were switched off and we slept on the station floor for many a night during air raids. I still have to resist getting undressed on platform three when I go down there to catch a tube train home from Soho.

I have a vivid memory of VE Day when the war was finally over. I was nine and my cousin Alan – who was five years older than me and was my boyhood hero – took me to join the celebrations on the streets of the West End. There was much spontaneous singing and dancing and I particularly remember a sailor. I assume he was a sailor because he was completely naked other than wearing a sailor’s hat, his modesty barely covered by a skimpy Union Jack flag, as he pulled us into a circle of revellers for a knees-up.

Once the war ended, my grandparents’ flat in Bedford Square was very much the focus of family life. We were a close-knit bunch. Grandpa Peter’s brother Nussan had married my grandma Annie’s sister Brandel. In the next generation, my father’s brother Hymie had married my mother’s sister Betty. Don’t spend too much time trying to work that out, just be assured that there was no incest involved down the line. I was very close to my cousins Alan and Marlene Myers on my mother’s side and Roy and Patsy Bloom on my father’s side and we were socially pretty much self-contained. I had other cousins who were born after the war but we never had the opportunity to be that close. I was never that involved with my grandparents on my father’s side, maybe because my father was not close to them himself.

On Thursday evenings my parents and my aunts and uncles, together with their children, all met at the Levenbergs’ flat at Bedford Court Mansions. I have wonderful memories of the warmth and closeness of those family gatherings. Parents, uncles, aunts and cousins, eating, laughing, shouting and more eating. Grandma was a great cook.

When my cousin Alan was sixteen, his best pal was Marty Feldman, who used to come to my grandparents’ flat and practise his clarinet – my first introduction to show business. Alan also introduced me to jazz and American big band music at a very young age, for which I thank his memory.

My father had worked as a hairdresser before the war and when he was discharged from the army in 1945, he got a job at a Mayfair salon. He was, by his own admission, a lousy hairdresser and claimed that his inept use of scissors inadvertently produced asymmetrical haircuts long before they became fashionable in the swinging sixties.

In spite of – or maybe as a result of – my patchwork education, aged eleven I passed my scholarship exams and spent a term at East Ham grammar school, before the family moved to Finsbury Park, where I attended Holloway County grammar school.

2. THE FIFTIES – THE FINSBURY PARK YEARS

My mother had been in a

terrible traffic accident during the war and it was painful for her to stand, so being a hairdresser was not a great idea. My father was still a hopeless hairdresser and it was decided they should both change careers. In 1947, when we moved to Finsbury Park, my father bought a small tobacconist and confectionery shop.

Dad had an envious eye on his brother-in-law Len, who had three confectionery and tobacconist shops in north London. A multi-retailer! My parents had no capital and Len altruistically financed my father’s acquisition of the Astoria Candy Stores, a small outlet opposite the Astoria cinema on Seven Sisters Road.

The Astoria was a showpiece cinema built in the thirties and was decorated spectacularly in the style of an Andalusian palace. There were silhouettes of Andalusian architecture around the auditorium and a large mosaic fountain in the foyer. When the house lights went down, the roof was a beautiful dark sky twinkling with stars. It was truly magnificent. I had a free pass to The Astoria – if you kicked the third emergency exit door on the Seven Sisters Road side in the right place, it would open and allow you to pass freely into the splendid auditorium. In later years The Astoria would become The Rainbow rock venue and I would promote shows there. The first thing I did when I took over was to secure the third exit door on the Seven Sisters Road side. It is now a church and you can get in for free. Where’s the fun in that?

Finsbury Park now has the wonderful Park Theatre, opened in 2013, a two-minute walk from where I once lived. Many years later I produced plays there. You can take a boy out of Finsbury Park, but you can’t take Finsbury Park out of a boy.

My dad had a board outside our sweet shop that advertised the current weekly variety bill at the nearby Finsbury Park Empire. For this we were given two tickets for each of their weekly shows and I saw most of the acts that played there. There was always a mixed bill of supporting ‘specialty acts’, known in the trade as ‘spesh acts’: jugglers, acrobats, magicians, cycling acts, dog acts, knife throwers … Variety in the true sense of the word. Table tennis was very popular at the time and Viktor Barna, the Hungarian world champion, used to tour the halls giving exhibition matches. Artists such as the Beverley Sisters were advertised as ‘Decca Recording Stars’ in recognition of having received the great accolade of a record deal, and comedians famous through radio often topped the bill.

Hunky Dory (Who Knew)

Hunky Dory (Who Knew)