- Home

- Laurence Myers

Hunky Dory (Who Knew) Page 6

Hunky Dory (Who Knew) Read online

Page 6

I know that I have already told you how much of my business success I owe to Allen, but I am saying it again, so there, and it all began with the EMI deal he secured for Mickie.

Now that Mickie was fully financed by EMI, the Rak Records group really started to motor. In addition to continuing with The Animals and Herman’s Hermits, Mickie produced records with Lulu, Jeff Beck, and Donovan. Most of the songwriters already had a publishing deal, but the hope was that Rak Publishing, headed by Mickie’s brother Dave, would pick up the rights on some of Mickie’s records. Mickie was very smart and he never let the publishing rights influence his choice of songs.

In June 1966, I was asked to conduct an audit of Pye Records, on behalf of The Kinks. The Kinks were currently hot with ‘Sunny Afternoon’ and ‘Dedicated Follower of Fashion’, written by Ray Davies. They were, I thought, original songs and Ray sang them in his natural London accent, which I found a delight at a time when guys who spoke broad Geordie sang like they were born in Mississippi. As a fan, I was eager to meet Ray. They say never meet your heroes and avoid disappointment, which isn’t always true, but in Mr Davies’ case it was. Considering that he had written ‘Sunny Afternoon’, Ray turned out to be less than sunny. This is something that others have remarked upon. Years later I met with Ray again to discuss the possibility of him writing a stage musical and charming he was not. Some would call him taciturn; I would call him a miserable bastard but not – of course – to his face.

The Pye audit was most revealing. Amongst other more minor discrepancies, the good old ‘payment on 90 per cent of sales’ came up. This anachronism of royalty reduction for breakages in transit, when records were no longer inclined to break, was standard in contracts of the time. What I discovered was that the Pye accounting system took 10 per cent off all sales before the income was reported in an artist’s account. They then took another 10 per cent off royalties payable to each artist. As I mentioned earlier, it was institutional cheating. Most of the record companies were established icons, and the thought that they would be in any way dishonest was outrageous. In more recent years the same could be said about high-street banks.

10. THE GREEK TYCOON

Although this story is more to do with my life in film, Allen Klein was integral to getting The Greek Tycoon made as a Hollywood movie made so I will tell it now.

In 1976 I was really in the movie business. My record companies were doing well and I had started GTO Films in 1974. It was a major player in the UK film scene and we always had a big presence at the Cannes Film Festival. Allen had dabbled in the movie business – mainly spaghetti westerns – but we had never tried to do any films together.

Some few months earlier, Nico Mastorakis had been in my office trying to sell me some low-budget, soft-porn films that he had made in Greece. I declined his offer as we did not deal in pornography – obviously a huge mistake. Nico, a small-time writer/producer had had a career as a TV personality in Greece, but I later found out that it was during the time that his country was governed by the right-wing military junta so he was not particularly popular in Greece by the time he came to see me. He asked what sort of thing I was interested in. I said broad-appeal commercial movies. Nico rummaged around in his bag like a travelling salesman and after examining a few scripts produced a film treatment entitled Onassis. ‘What about this?’

He wanted to write and produce a film of the life of shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis and needed seed money to get the project under way. He had, he said, a commitment from Anthony Quinn to play Onassis. My disbelief was obvious so Nico asked me if I would like to speak to Quinn directly, right now, and get his confirmation. Of course I would! Right there and then, Nico made a call to Rome. In no time I was talking to Anthony Quinn who – having convinced me that he was indeed that Anthony Quinn – confirmed that, subject to script, director etc, he was eager to make this movie.

I had not so long before this read Willi Frischauer’s wonderful and fascinating biography of Onassis. Onassis – a charismatic figure who had been the richest man in the world – had died in March 1975, so he was still very much of interest to the general public. I looked at Nico’s treatment, which was obviously stolen from the Frischauer book. Nico insisted that the information was the same because Ari, as we were both now calling him, had told them both his life story. Nico explained that when he was a journalist he had ‘interviewed Onassis extensively’. As I recall, Nico confessed that the interview was him with a group of other scrambling photographers snatching a paparazzi-type photo of the great man and being removed by bodyguards before he could get a question in. Internet research reveals that Nico smuggled himself onto Onassis’ yacht as a musician and hid a camera behind his guitar strings while Onassis was entertaining Teddy Kennedy. He was discovered and thrown off the boat. Nevertheless, I was interested. I just knew that we mere mortals are fascinated with the lifestyles of the rich and famous, and Onassis was as rich and famous as they came. I doubted that Nico could write the script, but thought that finding someone who could would not be a problem.

The idea was that we would take Quinn to the upcoming Cannes Film Festival and – with the help of Bobby Meyers, a well-respected film salesman – we would create enough pre-sales of the movie to get it financed. The budget for promoting the film at Cannes was not big. Nico had already met with important sponsors in Greece: the Epirotiki cruise line, the Metaxa liquor company and the Greek tourist office who, between them, would provide at no cost to us ‘the most spectacular party ever thrown’ at Cannes. All I needed to finance was travel and the publicity campaign. Believing this would not cost more than ten thousand pounds, I went to Athens with Nico to obtain confirmation from responsible authorities that what he had told me was true. And it was. It was all very plausible.

Epirotiki had Cannes as a stopover on their scheduled route. Their five hundred passengers would disembark for an evening ashore and we would promptly board the passenger-free vessel for our party. As the ship provided catering three times a day already, our party guests would not be a problem. The tourist office loved the idea of a film showing the glamour of Greece. They promised to give us goody bags for our guests with ouzo, brochures, food samples and worry beads. They could not do enough. We met with Mr Mataxa of Mataxa spirits fame, who promised to provide enough ouzo for us to fill the swimming pool. I could see the headlines, as film starlets cavorted in my ouzo-filled pool. It was all just wonderful and did not impact at all on my ten-thousand-pound budget.

Back in London, I spoke to Quinn’s agent and said that I wanted to contract Quinn before I went to Cannes. No problem, they said, but I would have to pay 10 per cent of Quinn’s fee up front. This was thirty thousand pounds. I was now completely carried away. In for ten grand – in for forty. I sent the cheque. I then found out that Quinn’s agent also represented Jacqueline Bisset. Jacqui loved the idea of playing Jacqueline Kennedy and – subject to script and director – she would also commit to the movie. Yes, she would go to Cannes with us to promote the movie. As with Quinn, I would have to put up 10 per cent of her fee. So that was another fifteen thousand pounds from my already-busted coffers.

Nico was in Athens where he arranged for well-known Greek actress Irene Papas to commit to play Maria Callas. There would be no upfront fee for Irene but we would have to pay for her first-class travel and accommodation for the film festival. Nico also arranged for a bouzouki band to come to Nice from Athens, courtesy of Olympic Airlines. We would only have to pay for the overnight stay of eight musicians. ‘Why not?’ I said.

By the time we set off for the festival I was in for around sixty thousand pounds, which is probably half a million pounds in today’s money. I had to mortgage my house to cover it. This was one of the few secrets that I ever had from my wife. The festival had to be a financial success or I would have to sell my family’s home.

Thankfully, once we arrived at Cannes, our project was a talking point for those in the trade and the party on the boat was the hottest ticket

in town. Invitations were delivered by foot soldiers to hotels. They would ask (bribe) the concierges but – huge mistake – we did not put the names on the actual invitation cards, only on the envelopes. The concierges sold the invitations (why didn’t I think of that?) and I was obliged to send out a further few hundred invitations properly addressed. There were now some eight hundred invitations in circulation.

Allen Klein was in Cannes for his own business and inevitably I received a call from my friend and mentor. He asked me if he could get involved in the film but I said no. Allen would not be capable of being a partner, he would have to run the whole deal, and I was determined not to abdicate control of this golden opportunity to break into big-time movies. I was honest with Allen about my thoughts on this and he was fine about it. He asked if he could read the script anyway and was surprised to learn that I had not got around to having one written.

There is a golden rule in filmmaking that the three essentials are: the script, the script, and the script. I was aware of this but before getting around to it I had lined up the stars, the stars, and the stars. I was the shmuck, the shmuck, and the shmuck who – like Sinatra – would do it My Way. In my defence, I would say that I had been spoiled by my reputation in the music business. If I had gone to a record company with, say, Tom Jones, they would have given me the deal knowing that I would find the right material and producer. But this was the film business and very few producers could get the finance for a film without a good script, director and cast attached and I was fairly unknown to Hollywood studios.

As if there was not enough going on for me in Cannes that year, I had to deal with Angie Bowie, who called me from London to ask if I could put her up for one night. She was David Bowie’s wife so I could hardly refuse. My head of distribution Bill Gavin was staying in a suite at The Majestic hotel and agreed to share with her. Angie arrived with eleven suitcases and ran up a phone bill the size of the national debt. She asked me if I could arrange for her to be the date of someone famous for a red-carpet film screening, which I could not.

Anthony Quinn arrived the day before the party. His Italian lawyer and one of his many agents were in town and Anthony suggested that Nico and I had dinner with them. He suggested the Moulin de Mougins – one of the finest and most expensive restaurants in the whole of France – and asked if my office could make the reservation. I said that it was impossible to get a reservation at the Moulin de Mougins during the festival as people booked from year to year but he said that he was a friend of the owner. Sure enough his name got us the reservation.

It was a fun evening. The restaurant was packed with people I knew and I rather enjoyed the kudos of sitting with one of the biggest stars in the world. Anthony was a great raconteur and regaled us with wonderful stories of the golden age of Hollywood. He carried on with his stories after we had finished dinner and – as entertaining as this was – it was getting late. With the big day ahead, I wished that he would call for the bill so that I could go home. The head waiter came to the table and informed Mr Quinn that his car was here. Mr Quinn stood up, thanked me for dinner and swept off with his guests leaving me with a bill which I remember could have paid for the dining room suite in my unfinished and now heavily mortgaged home in London. I subsequently also got the bill for his car.

I had sent Bill Gavin’s wife Jane to travel with the cruise ship from Naples to supervise the onboard arrangements en route. On the morning of the party, a distressed Jane called me from Naples with news from the captain. Firstly, the guests on the boat would have to stay onboard unless I paid twenty dollars a head shore supplement. If they remained, the maximum number of guests allowed to attend my party would be two hundred and fifty. I had sent out eight hundred invitations! I had written confirmation from the owners of the boat that I could invite five hundred people and told Jane to inform the captain of this and that I refused to pay any shore allowance.

We had planned that the ship’s tenders – smaller boats used to transfer goods and people to and from shore – would collect my guests from the jetty of the Carlton hotel. This was printed on my eight hundred invitations. But the captain said now that the tenders could not be used at all. Only tenders licensed by the Cannes municipality would be allowed. I was given the name of the man I should contact in Cannes to discuss this, a Monsieur Davide, from Havas Travel. I had written confirmation from Epirotiki, the boat’s owners, for using the boat’s own tenders and told Jane to inform the captain that I would ensure that the bill from Havas was sent to them.

Pretty sure that Havas would not send the bill to anyone other than me I rehearsed what I was going to say to Monsieur Davide. ‘Bonjour, Monsieur Davide, je m’appelle Laurence Myers et peut-être que je ferai une grande soirée ce soir,’ etc.

I telephoned Monsieur Davide on the dot of nine that morning. ‘Bonjour, Monsieur Davide, je m’appelle Laurence Myers et peut-être …’ He interrupted me immediately and in perfect English said, ‘Ah. Mr Myers, I was expecting your call. You are the gentleman who is obliged to hire our tenders this evening. Time is short, I suggest you come and see me immediately.’

I jumped on my little Honda motorbike and drove like a TT rider to see the man. A thanksgiving turkey riding his motorbike to the butcher. On the way, I tried to estimate what this was going to cost me. This was the Cannes Film Festival, where a Coca-Cola cost a week’s wages and the local sport was ripping off festival attendees. By the time I hurtled in to see Monsieur Davide, I was near hysterical. Trying not to sob at his feet I maintained a calm exterior. Monsieur Davide had already worked on the ‘petit problème’ and gave me the ‘grande image’. The cost of the tenders was six thousand pounds for taking two hundred and fifty people to the boat from the Gare Maritime (not the Carlton’s jetty), and he had strict instructions to take no more. Then there were the buses that I would need to take the people who would be following their invitations’ instructions to gather at the Carlton jetty to the Gare Maritime, a mile or so away. That was another thousand pounds. So a total of seven thousand pounds needed to be transferred from my bank account before a single tender pulled away from the shore. Wishing to be helpful, Monsieur Davide would accept a telexed confirmation from my London bank that the transfer had been made.

Back at my apartment, I called my bank in London and persuaded them to send the money from my already overdrawn account. I then summoned a council of war, attended by my partner Nico Mastorakis, Bill Gavin, and Dennis Davidson our PR. It was impossible to change our arrangements at such short notice and anyway Nico had telexes confirming the boarding arrangements that had been agreed with the ship’s owners. The telexes were in Greek – obviously Greek to me – so Nico telephoned Athens and tried to resolve the issue. Nobody at the shipping line would take his call. The rest of the day was spent sending costly foot soldiers around all of the hotels with costly (everything at the Cannes Film Festival is costly) flyers informing guests that the departure venue had changed.

I had lunch with Anthony Quinn and Jacqueline Bisset who – having no knowledge of the ‘l’heure des crises’ that I was dealing with – chatted happily about the project as I sat with a fixed and foolish grin on my face, counting in my head the cost to date of the ‘free party’.

In the afternoon the bouzouki band called from Rome. The free tickets provided by Olympic Airlines were only valid for the Athens–Rome leg of the trip and I would have to pay for the Rome-Nice leg. By now I was simply nodding at any requests for money, provided they could be met by my credit cards.

At eight o’clock in the evening, my stars were in the bar of the Majestic hotel, drinking the finest champagne my money could buy. Eight hundred people were lining up at the entrance to the Gare Maritime singing, ‘Why are we waiting?’ in an assortment of languages. The invited TV cameras and paparazzi were waiting on the dockside and patrolling the waters in hired boats ready to board the ship pirate-style. Bill Gavin was at the Gare Maritime, offering the captains of the tenders obscene bribes to take all of the gues

ts out to the ship. Monsieur Davide was grabbing the money from their hands and giving it back to Bill, who gave it back to the tender captains as soon as his back was turned. Allen Klein was asking if he could bring a couple of extra guests to the party. Of course he could!

Originally, the cruise ship was due to arrive in Cannes at five in the afternoon. We then received a message saying that it would not arrive until 7 p.m. It did not. At 7 p.m. I was standing at the edge of the quay, scouring the empty horizon. I might have thrown myself into the sea had I not been wearing my new white film producer’s suit. At 7.15 p.m. the ship arrived. Too big to dock in the port, she moored close by.

I hurried the advance party onto the first tender out. This was Quinn, Bisset, Papas, the bouzouki band and me. Everybody wants to be a star in their own country and Nico was heavily engaged with the Greek press. We arrived alongside the ship where there was a proper boarding platform manned by smart sailors. I felt a little better. I was first up the ladder. My first sight was the deck beautifully decorated with fairy lights and a vast spread of party food. I felt a lot better. My guests would party ‘till dawn’ as stated on the invitations.

My second sight made me feel worse. A prominent notice at the top of the boarding ladder stated ‘ALL SHORE VISITORS MUST BE OFF THE BOAT BY 10.30 P.M.’ There was a man with lots of gold on his uniform nearby, repeating the message, over and over again. ‘What does this mean?’ I asked. He read the notice out slowly as if I was a child.

‘Oh no,’ said I. ‘I have a contract. My guests will be dancing ’till dawn.’

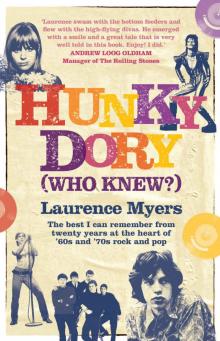

Hunky Dory (Who Knew)

Hunky Dory (Who Knew)